ICOs, Tokens and Token Valuation. A Quick Overview

1. What are tokens?

Very succinctly put, a token is a digital asset.

Just as with the regular use of the word, a token is a symbol of a certain amount of something, usually money. In the real world, a token is, for instance, a coin you can use to buy coffee from a vending machine or play the roulette in a casino, but you would still have to buy that token with “real” money.

In the crypto world, tokens are units of value, privately issued digital assets built on the platform of a certain cryptocurrency. Sounds complicated? We’ll clarify that in a second. But first, before you ask “What are tokens?”, you should clarify another question: “What are tokens for?”.

2. Where do tokens come from?

2.1. The very beginning

The history of the token starts with the history of the blockchain and Bitcoin.

When Satoshi Nakamoto presented his concise and elegant “Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” to the world in 2008, he revolutionized digital payments in 8 pages. However, it’s likely he did not quite know the amplitude of the revolution he set in motion.

What he thought he was doing was to create a network on which a new coin would be minted by a community of interconnected nodes, without the need for a trusted third party.

What he did was, in fact, to create a platform for sharing and storing data of any kind, from hashing blocks to create digital money to frictionless transactions between traders, and from recording complex chains of logistics or digital rights information to supporting innovative applications without moving a single cent of fiat currency.

The blockchain he created (without ever naming it as such) was, in fact, the cornerstone in the revolution. Based on it, other blockchains and applications were built, other cryptocurrency minted, and other ways of further revolutionizing financial transactions were developed.

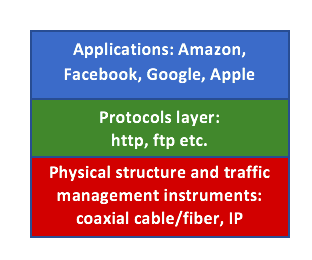

Because of the new possibilities incorporated in newer, nimbler blockchains, a new type of product was developed on a layer that had previously been impossible to monetize on: the protocols layer.

The protocols layer is that on which the user interface is built. Beneath it is the physical structure of the internet, fiber, coaxial cable and the rest, as well as the access protocols we are tangentially aware of: IP addresses, traffic management etc.

On top of all these layers sit the applications, the layer we are most familiar with, where the user interaction occurs. Here are the http addresses, the websites we access, the layer that belongs to Amazon and Facebook and Google, where the money is made and real-world transactions are conducted.

Until the creation of the blockchain, the end user could have no access to the middle layer, that of the protocols. As a customer of an e-commerce website, for instance, you have to trust the e-commerce website to either fulfill your order or refund your money, and you also have to trust national and international legal entities to correctly arbitrate any potential dispute.

Blockchain technology changed all that. It basically allowed you, the end user, to be part of the layer from which the transaction and the contract originate. In other words, you no longer have to trust anyone else to fulfill a transaction: you have access to the ledgers, as does anyone else in that ecosystem.

2.2. Smart contracts, DAPPS, DAOs and the birth of tokens

This level of transparency and decentralization can be used for transactions of either cryptocurrency or any type of asset or value, for sure. In fact, Bitcoin has allowed, from the beginning, for a certain level of complexity in what type of computational instructions are allowed on its blockchain. However, its language is Turing-incomplete, i.e. quite restrictive.

In 2013, a teenage blockchain entrepreneur by the name of Vitalik Buterin, the father of Ethereum, together with Mist Wallet co-founder Fabian Vogelstellar, imagined a way in which the blockchain could also incorporate, on a much larger scale and much more easily, what is called self-executing smart contracts.

Smart contracts had existed before, even before the invention of Bitcoin, but the new blockchain technology allows for a much more complex version. They are, in fact, conditional transactions of the if-then type. Developers can use, for instance, Ethereum’s Turing-complete language to issue instructions, which then execute and act as autonomous agents, thus allowing for uses such as contracts and agreements between two or several users, digital rights storage and management, membership and supply chain management and so on.

In Ethereum, smart contracts rule. These smart contracts, i.e. sets of computational instructions that execute transactions on the network (of the kind referenced above), can be built by anyone on the Ethereum network. Other blockchains support smart contracts, as well, but Ethereum’s ERC20 is the most widely used standard.

On top of these smart contracts, developers can build their own decentralized applications (dAPPS). Instead of a website like Facebook connecting to the API (application programming interface) to extract information, a decentralized application built on the Ethereum blockchain, for instance, connects to – and incorporates – a smart contract that is compliant with its ERC20 standard.

According to Ethereum’s white paper, decentralized applications are of three broad types.

- The first category is financial applications, providing users with more powerful ways of managing and entering into contracts using their money. This includes sub-currencies, financial derivatives, hedging contracts, savings wallets, wills, and ultimately even some classes of full-scale employment contracts.

- The second category is semi-financial applications, where money is involved but there is also a heavy non-monetary side to what is being done; a perfect example is self-enforcing bounties for solutions to computational problems.

- Finally, there are applications such as online voting and decentralized governance that are not financial at all.

A decentralized application is, in fact, what Buterin called, in that same white paper, a “decentralized autonomous organization”. A DAO is a “virtual entity”, just like a regular company, with a set number of shareholders. Just as with a regular company, the majority of these stakeholders, i.e. a certain specific percentage determined at the outset, can make decisions on that entity’s assets and code. In other words, that majority decides on how to allocate funds both outside and inside the DAO, what sort of “investments” to make, what products to put out and what rules govern its conduct.

What are tokens to the blockchain DAOs?

In simplified terms, DAOs release tokens to fund their projects. These tokens are sold to investors and become a tangible proof of interest in that project. As we explained before, tokens are privately issued digital assets built on the platform of a certain cryptocurrency.

In other words, the blockchain that supports a certain currency allows for the creation of such tokens, to be used exclusively on its platform, in order to support certain projects that are launched on that platform. DAOs are, in many ways, like startups that use tokens to both incentivize investment and reward it once the project becomes profitable.

What are tokens to regulators?

One caveat if you are just getting acquainted with the terminology.

“What are tokens” may be a harmless question technology-wise, yet it is a very sensitive question in the context of regulation. There are several types of tokens out there, and how you categorize them depends on which angle you are interested in.

There are native tokens (pretty much the cryptocurrency itself, like Ether, Monero or Bitcoin) and application-issued tokens (which is what we usually talk about in connection to ICOs and token sales; these are most commonly issued through smart contracts on Ethereum, as discussed above).

There are utility tokens (again, usually issued through smart contracts, acting as guarantors of future access to the product/service that is being created, or, if you will, “digital coupons” for that future product or service) and security tokens (those that are backed by external assets, for which regulations are in place in the US and other countries).

2.3. ICOs

Generally, the mechanism by which decentralized autonomous organizations launch tokens is called an Initial Coin Offering.

The name clearly mirrors Initial Public Offerings, but the comparison only goes so far. To give you a broad idea, let’s just say that ICOs are a fund-raising mechanism by pre-selling crypto-equity for products to be developed – except the term equity is very loosely used here. Those who buy the tokens, i.e. shares in the future product, do not also buy a stake in the company. Buyers have no say in how the company is run or how the funds are spent.

If there is no real equity for investors, though, what tokens for and why do they still invest? How do they know where to invest, and what do they get out of their investment?

First of all, there are rules for ICOs. There generally is a complex white paper explaining the project, what the product will do and how, how much money it needs and why, and usually how it’s going to be spent. There is also a clear timeline for investing and a list of currencies you can use to buy the tokens, be they fiat currency, like dollars or euros, or certain types of virtual currency. Another key element is a list of ICO sponsors, a detailed description of the team or a similar proof of the qualifications and motivation for the stakeholders to carry out the project (as opposed to, you know, making off with the money).

Once the ICO has closed, the funding requirements are either met or not. If not, the investments made are returned to the potential backers; if the goal is met, the project is carried out.

Most ICOs, it should be noted here, are unsuccessful, as the space is already teeming with projects and a large percentage fail at the outset. On the other hand, there are notable success stories, the first and most notable of which is Ethereum itself (launched through an ICO in 2014), now one of the most successful crypto projects out there.

If successful, these early backers will see the value of their tokens rise enough that they can either hold on to it as a store of value or trade it at high margins. That, in itself, is the reward for token investments.

ICO investments should be made with caution and prior documentation. While almost $4BN were raised through ICOs, some projects turned out to be fraudulent, a few were hacked, and many simply fell through in the early stages. Initial investments are usually not exactly in the realm of fortunes, but it is still good practice to invest only as much as you can afford to lose – and to do your due diligence when contemplating an ICO investment.

3. What are tokens worth? ICOs and Token Valuation

Token valuation is hard. It’s hard for both stakeholders and investors, in fact. Much of the difficulty comes from the fact that this is new, but very fertile ground, with relatively little supervision hard-coded in the system. So, how do you know how the odds are stacked in a token sale?

If you want to get scientific with it, Chris Burniske, for instance, promotes a variation on John Stuart Mill’s equation of exchange (M*V=Q*P) that attempts to predict token valuation: M = PQ / V, in which:

- M = size of the token base (i.e. total amount of asset supply in circulation)

- V = velocity of the token (i.e. frequency at which the tokens are traded/spent)

- P = price of the token

- Q = quantity of the token being provisioned (unlike the case of real money, the token is both the product and the means of acquiring the product, which poses certain problems)

In other words, the token valuation should calculate the price times the quantity, and divide it by the expected frequency of trade. This is not a fail-safe equation, since there are a lot of unknowns out there, but it offers a more systematic approach to assessing the market potential of a crypto asset.

What are tokens reactive to?

There were hundreds of attempts at creating a predictive framework for crypto asset price fluctuation, and, since economists are always trying to predict new things on the basis of old things, they mostly used the traditional approach of looking around to see how the real and virtual environments are affecting cryptocurrency. Starting from these assumptions, a recent Yale University paper analyzed how cryptocurrency prices are really affected by the factors widely believed to influence them:

- stocks (are the returns on the cryptocurrency market compensated by the risk factors derived from the stock market?)

- the price of fiat currencies (AUD, CAD, USD, EUR, SGD, GBP)

- commodities (gold, platinum, silver)

- macro-economic factors (non-durable consumption growth, durable consumption growth, industrial production growth, and personal income growth)

The answer? They’re not. While there is some variance depending on the type of cryptocurrency (e.g. Bitcoin vs Ethereum), basically, Aleh Tsyvinski and Yukun Liu noted that two factors alone seem to influence the price of cryptocurrencies:

- momentum: when a cryptocurrency increases in value, it will tend to rise even higher.

- investor attention: crypto prices combined with the number of posts and queries for cryptocurrencies on social media and in search engines.

If you’ve been following the ICO boom and relative slowdown over the past year, you know that to be true. ICO valuation, as an EY report on ICOs discovered a while ago, “is often based on “fear of missing out” instead of project development forecasts and the nature of token”. FOMO fueled by marketing and crypto market fluctuation is a much more solid driver of interest in ICOs than real-world economics.

That only goes to emphasize the need for prospective ICO investors to perform due diligence before committing to anything. That’s good advice for anything out there, really (if you don’t read the terms of service when you sign up to, oh, say Facebook, you might be shocked to find it’s been selling your information for years). But it’s all the more important when you are not yourself going to scour the blockchain for smart contract details that might come back to bite you in a few months’ time.

3.1. Due Diligence

The good news is, you don’t really need to be a blockchain wizard. For the prospective token investor, there are rules of thumb, either intuitive or context-specific, that need to be observed.

The first thing to check when assessing a token sale is the project itself. Read the white paper, read the description, run online searches on every tiny detail:

- What is the idea behind the project? What’s the unique selling point, the value added, the market fit, the scope, the technology?

- Who is behind the idea? Not just who is technically going to implement it, but also, are there any interesting names associated? Famous backers or advisers on the team? Does the project team have the right credentials for the job, and are there any legal advisers?

- What are your rights as an investor?

Don’t forget to look at the risks associated.

- Is the technology solid? Is the project hacker-safe?

- Where is the company registered?

- Is the project even legal in your country? Is the field regulated in any way, and if so, it the project regulation-compliant?

- Also, is the idea original or are there going to be legal battles over concept and execution?

Then, examine the token that is being offered.

- What kind of token is it, and is it technically sound? What’s the token design, distribution, utility, how many tokens are being pushed?

- Is there an ICO cap, what is it and how was it set?

- What’s the likelihood these tokens are going to gain significant velocity (i.e. be traded repeatedly in significant amounts)?

3.2. What are tokens to the regulating bodies?

We mentioned before that you need to be aware of the regulatory constraints of tokens, which in the US, for instance, apply to security tokens.

In the US, tokens are evaluated according to the Howey Test, which, to simplify, consists of a four-point checklist.

– It is an investment of money: hardly ever the case with ICOs, if you want to be very exact about it.

– There is an expectation of profits from the investment: that depends on what you mean by profit. Sometimes the investor expects a benefit “in kind”, for instance right-of-use for a certain product, as much as crypto profit in itself.

– The investment of money is in a common enterprise: that, again, depends on what the law means by common enterprise. In most cases, it would probably apply to ICOs.

– Profit comes from the efforts of a third party: most analysts insist there is no third party to be considered here; the transaction is made by and brings benefit to the members of that specific crypto community.

What are tokens in the case of these four points? The answer is, we don’t really know yet. What most everyone ends up concluding, and this includes regulators such as the SEC, which continues to hesitate over how to react to ICOs and crypto in general, is that current legislation is unfit to deal with this new type of financial asset. In the long run, then, expect attempts at regulating this field.

The U.S.

The US market is now close to supervision by three separate entities: the SEC (if crypto assets are seen as securities), the CTFC (if cryptocurrency qualifies as commodities), and FinCEN (if developers and exchanges are seen as money transmitters, they are required to provide customer information to combat money laundering and terrorist financing). In expectation of these rules and regulations, most exchanges in the US are attempting to comply with AML/KYC requirements, and ICO companies are attempting to preempt a closer examination by the SEC by declaring their tokens not to be securities.

Europe

In Europe, a wave of regulatory frenzy hit the most developed financial regulators early this year, with the German, Swiss and French financial supervisory authorities issuing guidelines on cryptocurrency and the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) warning that certain coins or tokens may constitute financial instruments, which would require compliance with the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (MiFID II) and the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AiFMD).

While European countries and EU regulators seem to adopt a somewhat more permissive attitude, regulation is still an issue and you need to check compliance before you invest.

Asia

Asian countries differ wildly in their approach to crypto and ICOs. China is extremely restrictive of both ICOs and cryptocurrencies, while South Korea is crypto-friendly, but has banned ICOs. Other countries, like Singapore, Japan and Hong Kong, are clear in stating that most tokens are securities and need to be regulation-compliant.

With all these caveats in mind, though, what remains is hard figures. With approximately USD4.8 billion invested in ICOs in 2017 alone, it has become clear that ICOs are not going anywhere. Despite an estimated 10% of ICOs falling prey to hackers and an untold percentage affected by fraud, as a mechanism for crowdfunding startups, ICOs are excellent business based on a sound principle: if it fails, you don’t lose; if it works, you win.